The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Suddenly Withdraws Link Connecting Cats to Bird Flu Transmission

In the new Trump administration's regime, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is causing a stir by concealing critical H5N1 bird flu information. This week, a peculiar occurrence took place in the CDC's revitalized weekly report, the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). A report suggesting that H5N1 can spread between cats and humans appeared briefly before being swiftly retracted from the online platform, as reported by the New York Times.

The now-vanished data, supposedly obtained by the Times, contained a table pointing to a potential human H5N1 case linked to a cat. The CDC has failed to provide any justification for the report's elimination or an estimated timeframe for its republishing. The CDC's homepage now features a statement: "CDC's website is being modified to comply with President Trump's Executive Orders." No response was received from the CDC after Gizmodo inquired for comments prior to publication.

The Trump White House issued a sweeping order in late January, compelling agencies under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, such as the CDC, to halt almost all external interaction with the public. Though certain drug safety alerts continued, other crucial services such as the MMWR—a weekly repository of studies and case reports from CDC scientists and other professionals for decades—were disrupted during this lapse.

The suspension of communication lasted up until February 1, as claimed by the Trump administration. However, the MMWR finally reappeared this week, albeit in a diminished capacity. The official MMWR for February 6 included just two reports related to wildfires, marking a significant decline from the standard number of papers featured in previous editions.

Additionally, anonymous health officials revealed that the CDC had three reports concerning bird flu expected to be published in the MMWR prior to the communication shutdown, according to the Washington Post. These reports are now missing from the MMWR.

The aforementioned table in this week's MMWR reportedly highlighted two H5N1-related cat clusters. In one, a house cat might have transmitted the virus to another cat and a teenage individual, with the cat passing away four days subsequent to falling ill. In the other, an infected dairy farmhand might have spread the virus to a cat, as the individual exhibited symptoms first. Two days after the person's onset of symptoms, the cat became sick and perished the following day.

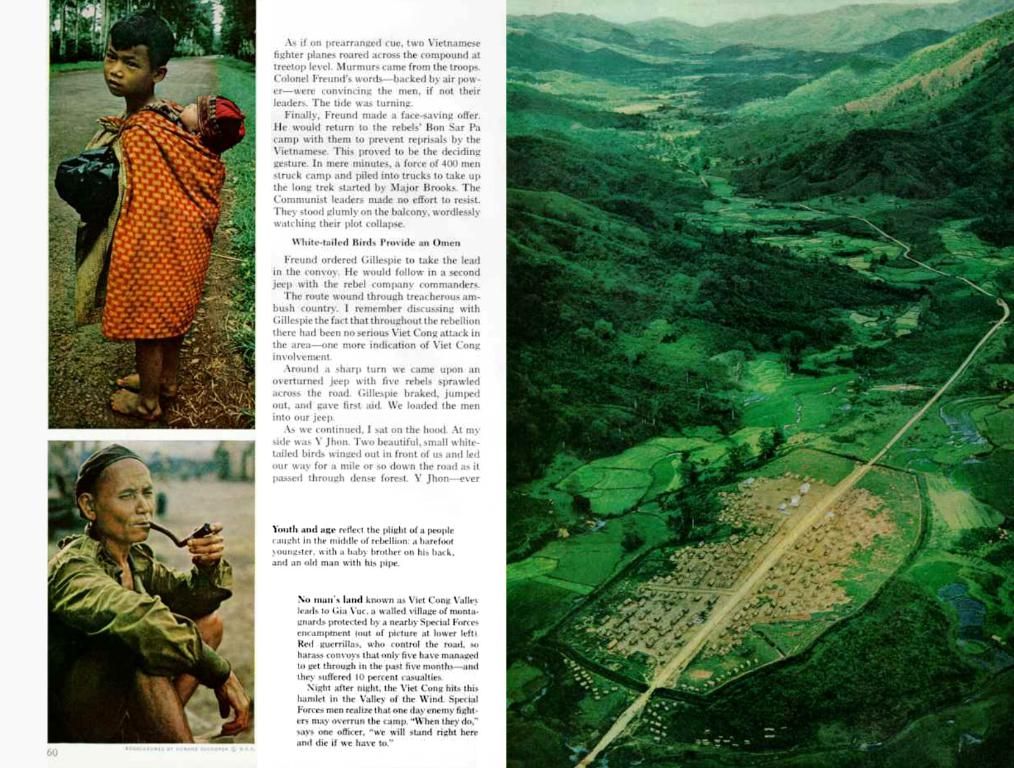

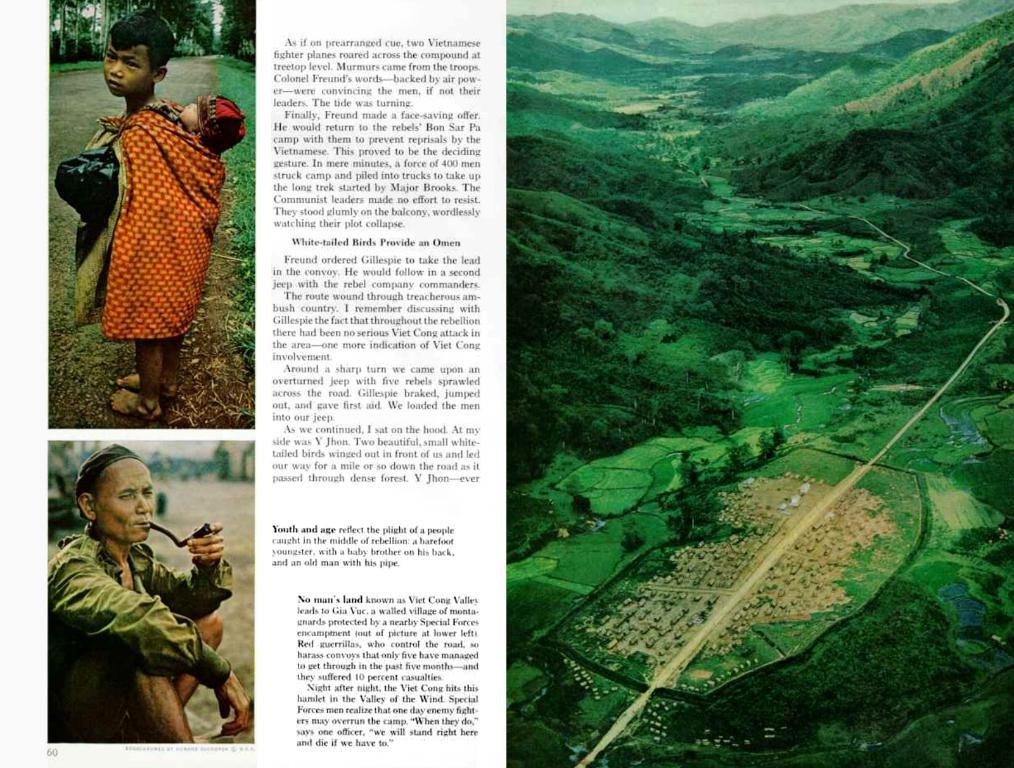

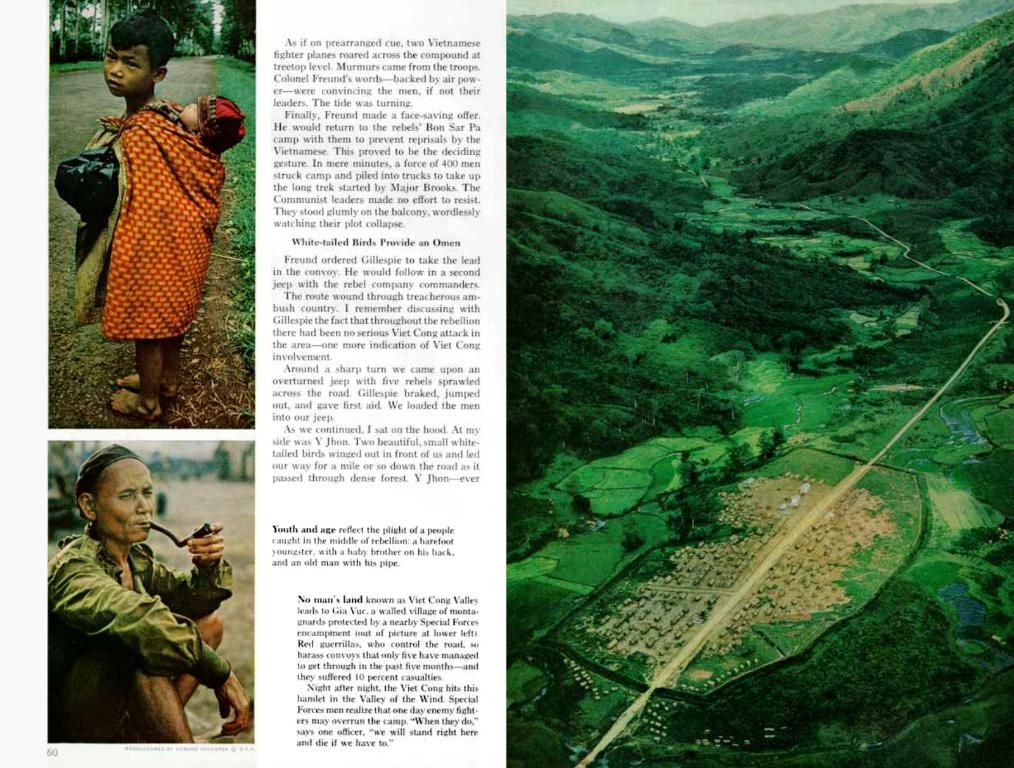

H5N1 has been a matter of concern for several years, escalating in early 2024 when a virus strain jumped the species barrier from birds, spreading among dairy cows. Around that same time, dozens of H5N1 cases in cats emerged, with cats being more prone to this virus than cows or humans. Cats can occasionally contract the infection from wild birds, and there have been cases linked to cats consuming raw milk or food sourced from farms.

Health authorities continue to categorize H5N1 and other circulating bird flu strains as a low risk for the general public. However, the lack of timely and detailed information regarding these cases remains a serious concern. Since the communication pause began, there have been several troubling developments related to bird flu.

For instance, the USDA recently discovered a novel strain of bird flu on a duck farm in California. This strain originated from an outbreak of H5N1, and the ducks were culled in late December. No additional cases of this novel strain have been reported since. Moreover, the USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service reported finding another type of H5N1 that jumped from birds to dairy cows—a type linked to more severe cases in humans than the earlier variant found in cows.

Though one such incident is unlikely to trigger a widespread, deadly strain of H5N1, the longer these viruses persist and mutate in mammals, the higher the risk becomes for a potentially pandemic-inducing strain to emerge. The uncertainty surrounding when and if the CDC and other agencies can keep the public adequately informed about H5N1 and other health threats is a valid concern.

The potential implications of H5N1 spreading between cats and humans is a topic of interest in the realm of future health and science, given the CDC's abrupt removal of a related report from the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The Trump administration's focus on technology, as evidenced by the Executive Orders affecting government agency websites, raises questions about transparency and access to critical health information.